(home)

a genesis,

a new beginning

where it began, ended, and everything in-between.

The steam from the fried rice warms my cheeks as I carefully open the thermos my mom had packed for me. Sliding the chopsticks out of their wrapper, I break them apart. The snap echoes harshly, an unfamiliar sharpness amongst the rounded edges of a midwestern elementary school cafeteria. A group of girls sitting nearby glance up at me and giggle. I’m not sure why they’re laughing but it doesn’t feel like the good kind. Clenching my chopsticks tighter until my knuckles turn white, I begin to eat my soggy noodles.

I was born in China and adopted at thirteen months in 2002 by my two mothers. My life before this is a blank space, an unknown. The orphanage that I was adopted from sent my parents off with two baby pictures, a Chinese birth certificate with a name that is no longer mine, along with a rough “estimate” of when I was born. I have no more information other than that that I was found in an (undisclosed) factory locker room as an infant and was shuttled into foster care until my adoption. There was no note found with me, no indication of who my birth parents were, what time I was born, or where. I was a nameless baby, a blank slate in which the world could mold as it pleases. I suppose that’s where my real story begins–– the day of my adoption. The day that my life changed forever.

I always felt it–– this uncomfortableness, sticking to the back of my neck like an unwanted sweat. “Too Asian” to pass off as white, “too white” to pass off as Asian. Stuck in mid-western suburbia, I wondered if I’m all middle and no edges.

I. birth (unknown)

II. in limbo

I always hated the yolk of an egg. That yellow, dry crumbly bit surrounded by the better white part. I hated the way it got stuck in my teeth only to be painstakingly scraped out by the tip of my

tongue. I hated the way it lingered in my mouth, and no matter how much I brushed it still coated the back of my throat. Like the inescapable stench that it leaves behind in your mouth, I couldn’t escape the yellow that defined me. Carefully separating the yolk every single time, I choked on those egg whites.

My parents brought me home from China, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. There’s a picture that my mom took of me on the plane ride to the States that she always pulls out during birthdays and family reunions, and I can’t help but look at it with unfamiliarity. Who is this baby? Is that really me? Am I the person that this baby would become? Would this baby become someone different if her life had been different?

When I look at this baby, this fleeting version of myself, I see finality, I see the ending of a chapter that has barely even begun. I mourn for this baby, this child who wasn't wanted. But when I look harder, I can see a new beginning on the horizon. I see rebirth, I see the start of everything.

III. limbo pt. 2

I spent the early years of my childhood in a gritty neighborhood, Logan Square, on the northside of Chicago. We lived on the top floor of the low-rise apartment building that my parent’s owned. My memories of this time consisted mainly of walks to the nearby Italian ice shack to get lemon sorbet in the summer and counting the ladybugs that nested in my bedroom window during spring. I would play games in the front yard, using the water pipe that snaked through the grass as a dragon that would take me to faraway lands. Every night I would lull into quiet dreams, pulled into sleep by the comforting hum of the nearby trains. I long for these moments, the ones that slipped by so quietly. When I was six, my mom Jill got a new job in Shaker Heights, Ohio. We packed up our belongings, said goodbye to our family, and said goodbye to Chicago.

IV. change / shaker heights

In sixth grade, my class hosted a foreign exchange student for the year. His name was Haruto, and he was from Japan. Including Haruto, my school only had a handful of Asian kids within a student body of over 1,000. Unsure how to communicate with him, my teacher assigned me as his guide, communicator and mentor. But I’m Chinese, I said. Close enough, my teacher said.

The isolation and alienation I experienced for being Asian (and for having lesbian mothers), cultivated a deep resentment of my culture within me. I felt like an outsider, an enigma that didn’t belong amongst this sea of white. My self-hatred, combined with the lack of exposure to my own culture, created an even

bigger disconnect and division between my Chinese

identity. I felt blurred, muted. I truly wanted nothing more than to escape myself–– I so desperately wanted to shed my own skin, to become someone whole. Unfractured.

On top of my confliction for being Chinese I also had to navigate the Mexican influences in my life as well, perhaps in some ways an even bigger question mark than my Chinese side. My mother, Katherine, and her entire side of the family are Mexican. Instead of hot pot, I grew up eating tamales and arroz con leche. I remember falling asleep to telenovelas and sleepy “te amos.” I was always at a crossroads of my identity, unsure of who I was and where I belonged. Am I Chinese? Am I American? Am I Mexican? Even my name, Catalina De La Peña, serves as a permanent reminder that I am merely a reflection of what’s been given to me. My original birth name, Ying E, was a randomly generated name that the orphanage assigned to me. Both Catalina and Ying E feel foreign to me, not quite mine.

Jill and I, Puerto Rico 2004

When I was little, I had an obsessive love for bananas–– they were my favorite fruit. My mom packed me one every day, without fail, for lunch. There was this one time, in the fifth grade, when I had just sat down for lunch in the cafeteria. After pulling out my banana, one of my friends turned to me and started laughing. What? I had asked. I just realized, he said through choked laughter, that you kinda look like a banana. There it was, that uncomfortable feeling that spread on the back of my neck like burning static. I guess so, I said, cheeks burning red.

I lived in Ohio for six years, from the age of six until I was twelve. I remember feeling like a foreigner–– someone untethered, a fractured reflection of a million different things that seemed impossible to put back together.

When I was twelve years old, my mom got a job offer in Chicago that she couldn’t pass up. So my family and I moved back to the windy city, where we lived until I graduated high school. When we were in Shaker Heights, we never stayed in one place for very long, always bouncing from one home to the next. After we moved back to Chicago, to my relief, we bought a house which I consider the closest thing to my “childhood” home. I craved stability and familiarity–– a place to call mine. Chicago was, and still is, the one place that I feel tethered to. A nostalgic home of warm memories, a place where I belong.

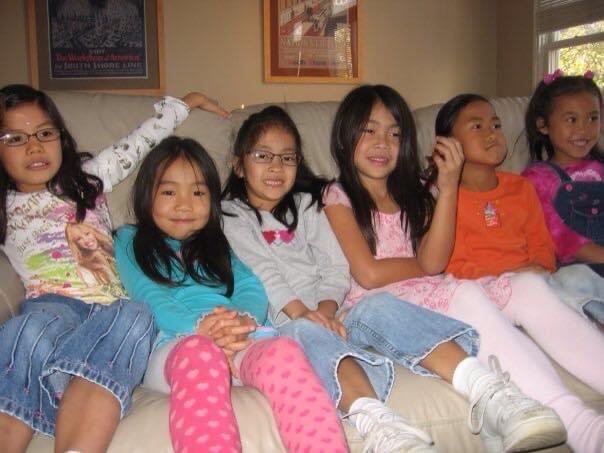

Six other girls from my orphanage were adopted the same I was. We all lived in Chicago, and we would come together every October (the month we were adopted), which we fondly referred to as our "Gotcha" Day. Our families call us the “Wu Sisters,” named after the city we were adopted from–– Wuzhou, China.

The Wu Sisters, Chicago 2008

We all still keep in touch to this day. It comforts me that the six of us share something so special, something that will tie us together for life. All of us are in college now, some stayed in Chicago, one went to Minnesota, another in South Carolina. It fills me with relief knowing we're all happy, we're all paving our own way through life. No matter where we go, what we do, who we become–– we'll always have each other.

From left to right: Lily, Maya, Lishan, Me, KJ, Nora, Meilin (unpictured)

V. the finale (but not really)

My relationship with my cultural identity improved as I grew older. I learned to cherish every part of what made me who I am, to celebrate the hard journey I have trekked to get to this specific moment in my life. I had finally gotten to a positive place within my journey of acceptance–– until the summer going into my junior year of college. For years, I had always wanted to take a DNA test. More so for my own peace of mind, a physical reassurance to all the unanswered questions that could only be answered through science. I figured, hey, why not find out what part of China my ancestors came from? So I ordered a 23andMe test from Amazon, spit into a tube, and waited with anticipation.

After 3-5 business weeks, my results finally came back. I wasn’t exactly sure what I was expecting to find, but finding out I am 85% Vietnamese and only 15% Chinese is a discovery that has changed my life, yet again. It felt like everything was crumbling before my eyes–– the narrative of myself that I so desperately tried to piece together, felt like a lie. I had always felt like a “fraud,” not Asian enough to claim as my identity–– always experiencing the “death” of my Chinese self. I didn’t know the language, I didn’t grow up eating Chinese cuisine, and my family was the furthest thing from an Asian household. Finding out that I’m Vietnamese was like the second death of my Chinese identity–– I was mourning the loss of something that I could barely claim as my own in the first place.

It’s been a year since I found out I’m Vietnamese. I’m still navigating this tumultuous journey of my cultural identity, a path that I will always be on in some way or another. I've learned that my unique identity doesn’t make me any less Chinese (or Vietnamese), and that it will always be a part of who I am. I’ve also learned that there’s more to me than my adoption, that this small part of my life doesn’t define me. Ultimately, finding out that I’m Vietnamese wasn’t the death of my Chinese self–– it’s the genesis, the beginning.

The "one-child policy" is a population planning initiative in China implemented between 1980 and 2015 to curb the country's population growth by restricting many families to a single child. Baby boys were favored over girls, because they could carry on the family legacy. An estimated 20 million girls went "missing" from China during this time.